For model-year 1965, Porsche wound down production of the 356 Coupe and Cabriolet and ramped up the assembly line of its then-new 911 coupe. While some open-air driving enthusiasts were likely concerned that roofless 911s weren’t offered at the model’s launch, these worries would soon be eased.

In September 1965, at the Frankfurt Motor Show, Porsche introduced the “Targa” version of the 911, which was named after the company’s many racing successes in the Targa Florio open road race in Sicily. But after this first showing the company took more than a year to put the unique, precedent-setting open-topped 911 into production.

Setting the Stage

Convertible models had come to enjoy a modest but steady sales rate since an open car was part of the very first Gmünd-built Porsche range. In 1960, in fact, they were 41.6 percent of total Porsche sports car production. The share was in decline, however, falling to 27.2 percent in 1961. This was the position at the beginning of 1962 when key decisions were being made on the new T-8 body that became the 901 (later renamed the 911 in October 1964).

From the outset, it was assumed that the T-8 range would include both a coupe and a cabriolet. This was enthusiastically supported by Harald Wagner, a nephew of Ferry Porsche and the domestic sales chief at Porsche since 1954, described by author Wolfgang Blaube as “the strongest cabriolet protagonist in Zuffenhausen’s executive suite.”

Both Gmünd and Reutter-bodied 356 Cabriolets were of natural notchback configurations, differing in this respect from their fastback coupe counterparts. “The system to open the roof of the 356 was completely developed,” noted engineer Eugen Kolb, “but nothing could be taken from it for the 901. If you copied the 356 roof system it would have been too high at the rear, like a Volkswagen and not like a Porsche.”

In addition, Porsche management’s presumption with the 901 was that the coupe’s lines should be only slightly altered because the open model was foreseen as enjoying only a small share of the production. This meant that an open 901 would have to use all the structure and rear sheet metal of the coupe.

Here designer F.A. “Butzi” Porsche found himself on the horns of a dilemma. Considering the fastback to be a dated concept, his affection for notchbacks was well known. Later Butzi was quoted about the Targa as saying, “To me, it should have been a pure cabrio alongside the coupe. I suppose any convertible looks better with a notchback; a fastback does upset the visual balance somehow. There has never been a successful rear-engined cabriolet with a true fastback.”

Nevertheless, when he set out the parameters for the creation of a T-8 cabriolet in his action memo of January 1962 to his design colleagues Butzi included the following:

•Demountable or fixed bow directly behind the door opening;

•Removable but inherently rigid roof element of metal or plastic, which can be stored in the nose space or a fabric cover that can be rolled up;

•Rear window of a transparent film with a zip-fastener attachment to the bow.

Here was a pretty fair country description of the Targa as it emerged from the development stage almost three years later. But its path to production was anything but smooth.

Choosing an Open-Air Setup

Action on an open version of the 901 was moved to a back burner during 1962 and the early months of 1963 to allow full concentration on the preparation of the final configuration of the coupe. By mid-year of 1963, however, the topic was current again. On May 28, Butzi summed up the various proposals for an open-topped 901.

One of the three options as he saw the situation was a “normal folding cabriolet with completely retractable elements on all sides.” This would offer all the amenities of such a convertible but would require more modifications to the components of the rear of the body shell than the other options discussed. Still on the agenda, in Butzi’s view, was the possibility of a notchback version, especially for the full convertible. As well, he said, full retraction of the car’s “rollover bow” would need changes to the body structure.

Another option, preferred by technical chief Hans Tomala, was a “simple roll-top roof similar to the Opel cabriolet sedans of 1933-35.” Its rear window would either be fixed glazing or transparent material held by a zip fastener. Although this would permit a built-in rollover bow it had the drawback that fixed members, carrying the fabric roof, would remain in place above the doors and rear-quarter windows when the roof was opened. A plus was that the rear seats would be fully available under all conditions, which Butzi felt would not be the case with the full cabriolet.

Butzi Porsche’s favorite remained the third option, a manually releasable solid panel between the windscreen and a fixed rollover bow, a design he had already modeled. He admitted the disadvantages that it could only be manipulated when the car was at rest and that some means had to be found to stow the panel on board without taking up too much luggage room. As with Tomala’s preference the rear window could be either removable or fixed. Engineer and fresh-air fiend Helmuth Bott argued persuasively in favor of the removable top option.

Common to all three proposals was the concept of a fixed or removable Rollbügel or “rollover bow” at the B-pillar behind the seats. Although mid-year 1963 drawings of pop-top 901s didn’t show this feature, it was integral to the three alternatives that were foremost in consideration at that time. “There are two excellent practical reasons for fitting a roll bar,” Butzi Porsche explained. “First, it meets U.S. competition requirements and second, this type of convertible can be controlled better when closed, whereas most tend to fill up and swell like air balloons.”

The most compelling reason for fitting a rigid hoop at the chosen location was its contribution to the integral body’s stiffness. Here the 901 was already at the margins as had been revealed by its structure’s initial failure during durability testing. Although based on that of the 356, which had been robust enough for both open and closed versions, the 901’s unit body had to cope with new patterns of impacts from a front suspension that had completely different attachments to the structure. Window openings were much larger as well.

Facing enough challenges with their 901’s coupe version, Porsche’s engineers had not taken the time to consider an open-topped version’s greater structural demands. “If you plan a new model in a fixed-head and an open-top configuration,” said veteran Porsche designer Wolfgang Eyb, “you logically have to start with the structural design of the latter and derive the former from it: cabriolet first, coupe second.” With the 901, he said, “we were asked to do it the other way around, which was completely impossible.”

This was proven beyond argument a year later, in mid-1964, when metal was finally cut on an open-topped 901. Convertible fan Harald Wagner prevailed in his arguments on behalf of a fresh-air version of the new model. While engineer Gerhard Schröder schemed suitable mechanisms for a full cabriolet roof, the Reutter engineers produced a body to accept them. This was chassis number 13360, delivered on September 10, 1964.

Equipped with one of Schröder’s roofs, this prototype cabriolet was tested and found wanting. “That car was never rigid enough,” recalled Wolfgang Eyb, “never rain-proof enough.” The solution had been there all along: the Rollbügel as championed by Butzi Porsche. It went far to maintain the lateral rigidity of the “shoulders” of the body, just behind the doors, that was usually provided by the roof structure. This was tried out on the prototype chassis 13360 and found to have the desired effect.

Whether, as suggested by the young Porsche, the boxed-steel hoop structure was acceptable to United States racing authorities was never put to the test, since the coupe version of the 911 was the one normally used for competition. But the rollover bar’s presence did permit Porsche to call the Targa “the world’s first safety convertible” well in advance of any effort by U.S. authorities to impose roof-strength requirements on new cars.

Soon after the Targa made its bow at 1965’s Frankfurt Show, one was given a drop test to validate the roll bar’s functionality. On November 10th an inverted Targa was dropped from a height of 6.6 feet. It failed this severe test. After engineer Werner Trenkler beefed up the structure an amended prototype was subjected to the rigors of VW’s proving ground and judged to be satisfactory.

Ironing Out the Details

That the new model had a distinctive name was Porsche’s response to a dealer’s suggestion that this unusual body style deserved an identity of its own. “We had to sell the car,” said sales chief Harald Wagner, “and to do that we needed a name. So we started with what we would call a brainstorming session.” He described it as follows:

“Someone had the idea that we should name the car after a race track but half the names had already been used and the others didn’t sound right: Daytona, Le Mans, Nürburgring. We discussed “Targa Florio” but we were worried that customers might start dropping the first word and abbreviating “Florio” to “Flori,” which sounded a bit effete. So then we thought, what if you took the “Florio” away completely?”

Startling, even bizarre in appearance at first, the Targa concept soon gained friends with familiarity. It set an example that was soon followed by other sports-car makers in Italy and America. Indeed “Targa” became the generic designation of open tops achieved by lift-out panels.

As for swelling up like balloons, the early experimental Targas were not immune to the problem. The initial plan called for a heavy transparent plastic rear window that would fit the space behind the roll bar and would be inserted or removed by means of zippers around its edges. This worked out well and the Targa was introduced with such a window. However, owners were warned not to unzip it at temperatures below 60 degrees Fahrenheit since the plastic shrank when cold, making it next to impossible to put the window back in again!

As confirmed by test filming on the road, ballooning occurred in the fabric panel that Porsche intended to insert between the windshield and the roll bar. This, together with the rear-window scheme, was covered in the patent applied for by engineers Tomala, Schröder and Trenkler on August 11, 1965.

The removable roof was still a work in progress at the Frankfurt debut in 1965. The plan was to offer two different kinds of panels for that area. One would be a rigid reinforced-plastic roof that would make the front portion of the cockpit into a snug hardtop. The other was a lightweight fabric panel that was to be carried in rolled-up form and used only for emergencies like a sudden rain shower on a sunny day.

The compromise of two different roof panels had been necessary because Porsche had not yet been able to come up with a single flexible fabric roof insert that would not be sucked high into the air stream above the occupants’ heads. Ferry Porsche and Wolfgang Eyb had a scheme that they patented, as did the team of Karl Vettel and Werner Trenkler with another concept.

Trenkler is credited with the solution to the ballooning problem in time for the Targa’s production. One roof insert was enough, a collapsible rubberized fabric affair. It had rigid side frames, above the windows, and front and rear cross-braces that could be folded scissors-fashion to tighten the fabric snugly when they were straightened and locked. This whole assembly plugged into two sockets in the roll bar and was clamped at two points to the windshield.

Although the roll bar was simply painted in prototypes it was given a brushed stainless-steel surface for production that contrasted with the rest of the body. “That idea was mine,” said Butzi Porsche. “I do think the roll bar has a function and adds stiffness—which is why it should be a different color from the car.” He granted that there had been criticism of the way the roll bar stood out visually, but he defended the concept in the strongest terms: “I think it looks better than one first thinks—and could be better still. Believe me, we weighed every consideration when planning the Targa and we have great hopes for it.”

It’s a Hit!

Butzi Porsche’s hopes were not shared, at first, by the Porsche sales department. Harald Wagner confessed that when he finally saw the Targa its styling “didn’t exactly knock me off my feet,” adding that the car looked like a 911 “defaced by giant metal stirrups.” However, he made good on his pleas for an open-topped 911 by taking Targas in the same proportion of his share of the production for Germany, about 30 percent, that he had always had in cabriolets. However, the works decided to produce only seven Targas a day out of a total daily production of some 55 911s when the new body style finally started moving down the line at the end of 1966.

One of the first Targas made was doubly historic. Produced on December 21, 1966, it was the 100,000th Porsche built. Destined for delivery to the state police of Baden-Württemberg, it carried a loudspeaker, flashing red light and police markings in addition to the traditional celebratory garlands. The use of the Targa as a police car was actively promoted by Porsche and had some success.

Even before the export markets had started to take Targas it was obvious, early in 1967, that demand far exceeded supply. Although production was stepped up to ten a day, this just kept pace with West German buyers’ demands, which were pushing the Targa to a 40 percent market share. Porsche executives suddenly realized that their new body style was a solid hit by any standards.

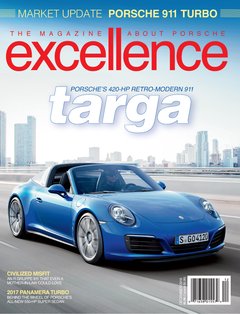

Based on the Type 964 platform, the last Targas of the original design left the production line in 1993. Their abandonment left capacity for a revival of the Speedster. Part and parcel of the rebooting of the 911 Carrera line with the Type 993 was a new model in 1996 with a sliding transparent roof panel. Although not at all analogous to the original Targa, the name lived on for this fresh version of the 911. And a new version of the uniquely configured model lives on to this day.