Brian Ferrin of Sonoma, California has been fortunate enough to have owned two early Porsche 911Ss. His stewardship bridges a lifetime of Porsche adventure. The odyssey began with a 1965 912. The little four-banger seemed affordable enough until it needed a new muffler. When Richard Pasquale, the parts counterman at Mozart Porsche in Palo Alto, California, told Ferrin how much a replacement would cost, starving student Ferrin turned catatonic. Only Pasquale’s offer of a job running parts for the dealership saved the day.

After Ferrin proved himself capable as a delivery boy, Pasquale promoted him to a full-time position behind the parts counter. Ferrin’s taste in Porsches escalated just as quickly as his career. Out went the 912, and in came his first 1967 911S.

But a devastating crash soon marred this first foray into six-cylinder ownership. Although his insurance carrier totaled the S, Ferrin had the foresight to buy it back from them for $500. Knowing that a perfect but stripped 912 was sitting on oil drums behind Mozart’s body shop, he bought those remains for $400. For less than a thousand dollars, he found himself in the restoration business.

Next to his parents’ house in Sunnyvale, California, Ferrin laid the wrecked 911S nose to tail with the stripped 912 and determined what parts were needed to restore the 911S, He then dissected the 912 as needed and knit one sound car from two distressed tubs.

Shortly after Ferrin started his career at Mozart, Carlsen Porsche took over operation of the Palo Alto franchise. To celebrate the change in ownership, Carlsen sponsored a Zone 7 Porsche Club of America (PCA) concours and swap meet that soon became an annual Bay Area institution. Ferrin did such a craftsman-like job refurbishing his wrecked 911S that it won the Best Car in Show trophy at Carlsen’s 1974 concours event.

By the end of 1974, he went to work for Anderson-Behel Porsche in nearby Santa Clara. Although only 22 years old, he had his sights set on buying a brand-new Anniversary Edition 1975 911S that retailed for over $13,000. He searched for a silver car with factory sport seats and found one at Wester Porsche in Monterey, California. Ferrin did a dealer trade with Wester, and then went down to Monterey to pick up the car himself.

“I didn’t want anybody driving my new car but me. I drove it home with the bags still on the seats. I still have the numbered dash plaque from that car,” said Ferrin. He kept the silver 911S for a year, sold it at a profit, and then bought a Gemini Blue 1974 Carrera.

A falling out at Anderson-Behel ended his Porsche career for the time being. He returned to college for a degree in Accounting and Finance at San Jose State. During those years, the Carrera was replaced by a 1973 914 2.0. After graduation, Ferrin went to work as a teller at the Bank of America. One day he was surprised to receive a phone call from Marj Green, co-owner with husband Tom Green, of the thriving Porsche parts distributor Automotion.

“I understand you were a really good parts salesman at Carlsen,” said Green, “and I was wondering if you’d be interested in coming to work for Automotion?” This opportunity would lead to a couple of golden years, which Ferrin remembers today with much affection.

According to Tom Green, Automotion started as a home-based business to help defray expenses incurred autocrossing the family’s 356 and 914-6 Porsches. But Automotion quickly expanded to fill a grass roots niche in the Porsche world that had long gone begging. By the early 1980s, the Greens had joined forces with Garretson Enterprises. Both firms shared the same building on Old Middlefield Way in Mountain View, California. About the same time that Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak were hawking their wares at meetings of the nearby Homebrew Computer Club, the Greens formed their own homebrew alliance with Bob Garretson called “The Winning Combination.”

While Brian Ferrin stocked Automotion’s shelves, Clark and Bruce Anderson, along with chief mechanic Jerry Woods, masterminded Le Mans and IMSA assaults for Garretson Enterprises’ 934 and 935 Porsche teams. The Winning Combination would later regroup to field Dick Barbour’s prodigious campaign on the World Endurance Championship, featuring Paul Newman behind the wheel. This was a very special time for all involved. As Ferrin recalls, the Golden Gate Region of the PCA was the unifying factor for all concerned.

“Not to diminish what the club is today,” said Ferrin, “but back then, GGR was really something special. Our teams were almost completely staffed with volunteers from the club.”

When work at Automotion shut down for the day, Ferrin would mosey over to the Garretson back shop to watch Jerry Woods assemble 935 motors, an experience that paid dividends in years to come. Said Ferrin, “I learned a lot washing parts for him.”

Although the Garretson and Barbour teams might have been racing Porsche products, these championship winning cars always carried a notation below the rear wing that read: “Made in Mountain View.” The other thing made in Mountain View was Ferrin’s marriage to Maggie, the gal who drove the UPS delivery truck on Old Middlefield Way back then. Their winning combination has outlived the other one by 30 years and counting.

After college, Ferrin’s accountancy training led to a CPA license which took him full circle back to Carlsen Porsche, now in a management position. Later, Ferrin became Sales Manager for Tom Claridge’s new Fremont Porsche dealership, ordering new Porsches, while running the used car operation. From this apogee of the Porsche lifestyle, a situation many of us would kill to enjoy, Ferrin decided to take another route in life.

From 1991 to 2003, he worked for American Express financial services. During those 12 years, he had virtually no involvement with Porsche cars, parts or people: “I decided to turn the page and do something different,” said Ferrin. Muscle cars, especially Mustangs, replaced Porsches in his fast lane.

But once he quit Amex and semi-retired to a rural spread outside of Sonoma, years of ingrained Porsche yearnings resurfaced like a radioactive half-life. He found himself scouring eBay for possible purchases.

“I started having the bug for another 911,” said Ferrin. “I decided a ’67 S was what I wanted, something to really take me back to my roots.”

This Thing is For Real

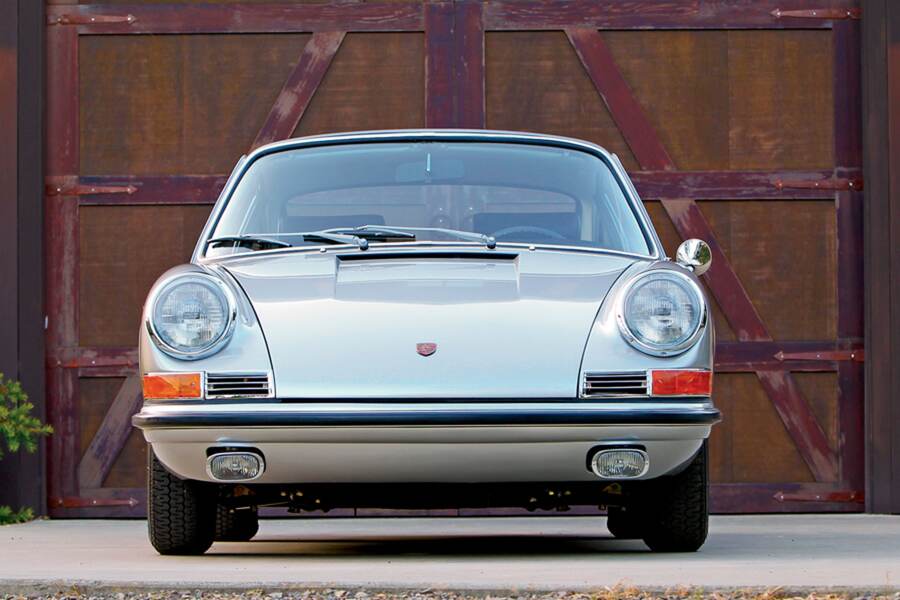

In 2005 Ferrin located a candidate in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: “It was a partially disassembled ’67 S,” he said. “Although it was repainted yellow, it had been born special order silver.” Ferrin hauled his truck and enclosed trailer north of the border where a deal was consummated with David Whittles for S/N 305-811, a 1967 911S carrying paint code 97/6206-1 on its left door post.

“The car looked good,” recalls Ferrin, “but it had been almost completely disassembled and there were some rust issues. The motor had been taken out and put in another car.” Despite that fact, he loaded up the tub, the disparate parts, and headed back to the border, where he was in for a rather rude surprise at U.S. Customs.

A customs agent’s cursory examination of the contents of his truck and trailer resulted in the observation that “We can’t have this. Lock it up and come inside.” In an adjacent office, Ferrin spent more than two hours explaining why his accumulation of parts was legitimate. When the Feds finally bought his reasoning, they insisted he would have to pay state tax on his purchase.

Luckily, he found a pink slip buried in the car’s paper trail that clearly showed that at one time, the Porsche had been purchased and registered in San Leandro, California “which got me out of paying any taxes.” Finally, at 1:00am, a beleaguered Ferrin was free to go. When he reached home in Sonoma, he unloaded his cache into an open fronted barn on his property. The 911S remained parked there for the next seven years.

For almost a decade, while Ferrin and his wife constructed a new house on their land, restoration of the 911 was the lowest thing on their to-do list.

“From time to time I would try to locate the original engine, but I was not successful,” said Ferrin. But with the help of a Kardex from Porsche, he did piece together the story of how SN 305-811 came to be parted out in Vancouver.

When new, the S was sold in September 1966 to a physician who was a citizen of the U.S. then working in Germany. After a year abroad, the doctor prepared to move to Alaska and had the 911 fitted with special skid plates under the heater boxes for expected snow driving. He shipped the car Stateside and kept it in Alaska until 1971, then sold it to its second owner who lived in Aptos, California near Monterey. This arrangement lasted for 10 years until a huge storm surge washed over the Porsche and its owner’s house, severely damaging both.

At that point, the water logged S was brought to a repair shop in San Leandro run by Athan Nikolou. Ferrin spent a year trying to get in touch with Nikolou: “I wasn’t trying to be a stalker but I couldn’t get him to call me back. But one day the phone rang and it was Athan. He filled in the rest of the story.”

The S required such extensive repair that when the job was completed, the Aptos owner couldn’t afford to retrieve his Porsche. He essentially gave Nicolou the car in exchange for the money owed on it. The shop owner decided to drive it himself, and did so for four years until he unknowingly fractured an oil line. Because he kept going without realizing the problem had occurred, all the oil seeped out and the precious S motor toasted itself. So he pulled the original engine and replaced it with a later 911E motor. Ultimately, he sold the car to the Whittles family in Vancouver.

Ironically the Canadians bought the car not because it was a rare early S, but because they needed its E motor for a Targa they were rebuilding. Once they extracted the E motor, the remains of the S became expendable. It sat forlorn in the Canadian garage for six years until Ferrin bought it.

Awakened after its seven-year slumber in the Sonoma barn, SN 305 811 was finally ready for the undivided attention of its owner. The first issue to address was that unoccupied hole in the engine compartment. Since the original motor was nowhere to be found at the time, Ferrin plotted an alternate course. His friends felt strongly that he should seek more displacement and horsepower.

“Everyone said, ‘Don’t put a 2.0-liter back in,’ they said, ‘put a 2.7-liter in,’” said Ferrin. “At first, I didn’t know whether I was going to make a hot rod out of it or not. But the most valuable cars are always the most original cars. I wanted it to be the way it was. I wanted to have the sometimes frustrating driving experience of a carbureted 2.0-liter S.”

With that decision made, Ferrin searched Craigslist for a replacement. There, he fortuitously unearthed, near Los Angeles, a 2.0-liter 1967 S engine less than 200 digits removed from the serial number of the original unit. He recruited a close friend of his living in Torrance, California to examine the find: “He said, ‘This thing is for real.’ So he bought it for me on the spot and took it home. From clutch to carb, it was 100-percent intact.”

Ferrin determined from the presence of original chain tensioners that the unit had racked up very few miles, “since those early tensioners rarely lasted past 40,000 miles.” But he was wary of using the engine as received: “The motor was in very good condition. A lot of the telltale pieces had never been apart. But I didn’t want to put an unknown motor into what was a known car. I rebuilt the motor myself. All that time working with Jerry Woods came back to me.” He also credits Wayne Dempsey’s book on rebuilding the 911 motor as a mainstay of the rebuild.

A brace of maroon colored factory 911 Parts Manuals that Ferrin picked up when dealerships migrated to microfiche were also essential tools: “I would never have built this car without those. The pictures, the information—those books are invaluable. They have those very nice German exploded diagrams, with everything oriented in its installed position. But more important for me, having sent a couple of thousand nuts, bolts and washers to the platers, every fastener is listed in those books, with length, thread, type of head, and finish. Without them, I would have had no way of knowing how to work on this. This was my bible for reassembly.”

The Early S Registry also proved invaluable as a source of information and recommendations for various phases of the reconstruction. Most of the sub-contractors Ferrin utilized were names provided by Registry members, forums or Jim Breazeale at EASY in Emeryville, California. Tony Garcia at Autobahn Interiors in San Diego beautifully restored the upholstery. After the Kardex revealed that his S was originally delivered with Houdstooth seat inserts, Ferrin tracked down the “last batch of original Austrian red, white and black Houndstooth” from a vendor in Oregon. He had the bolt of cloth sent to Garcia who used it to finish the seats and door panels.

Similarly, Ferrin went through five different suppliers for headliner material before the sixth finally could provide what he wanted: “None of the parts houses had the right material. Even Garcia said he couldn’t get the stuff.” Finally, he found a craftsman in Loomis, California: “He had purchased some of the original material years ago unperforated. He then made a machine to do the perforations. He had enough material to do two cars. Mine was one of them.”

After mounting the chassis on a rotisserie and stripping all the parts, Ferrin decided to send the body shell out for professional attention and paint: “I think I just didn’t understand what I was getting into with a bare metal restoration.”

From the Early S Registry, he learned that a nearby shop, then in Martinez, California, Freddy Hernandez’s Antique Sportscar Restorations, was ideally suited to the job of refinishing the Porsche in its special order original shade of 356 metallic silver. At the same time, he sent the petite Fuchs alloys off to Oroville, California, where Harvey Weidman returned them to their original splendor.

With help from prior owner Athan Nicolou, Ferrin finally located the car’s original S motor, and as he puts it, “We’re sort of working together to get it back. I would love to have the original sitting there so if I do take it apart again somewhere down the road, I can say, ‘Here’s the motor it was born with.’”

When the S was purchased back in 2005, Ferrin envisioned the finished product as something he wouldn’t hesitate to drive on a regular basis. But over the intervening years, early S prices have gone ballistic, and the thought of exposing SN 305 811 to undue trauma is off-putting.

“When I bought the car and the motor that’s in it, the sum total of those two purchases was maybe six to seven percent of today’s value,” said Ferrin. “In 2005, a very nice early S could be bought for $30,000-50,000. Here we are in 2015 and in some cases there’s a $250,000 value. So I’m just not going to joy ride it. I’m afraid to drive it sometimes. I would love to enjoy the car more, but it’s a different world than when I had my first 911S.”

Of course, if he hadn’t driven his Porsche to a Cars and Coffee meet, you wouldn’t be reading this story right now.